What Is Bloatware?

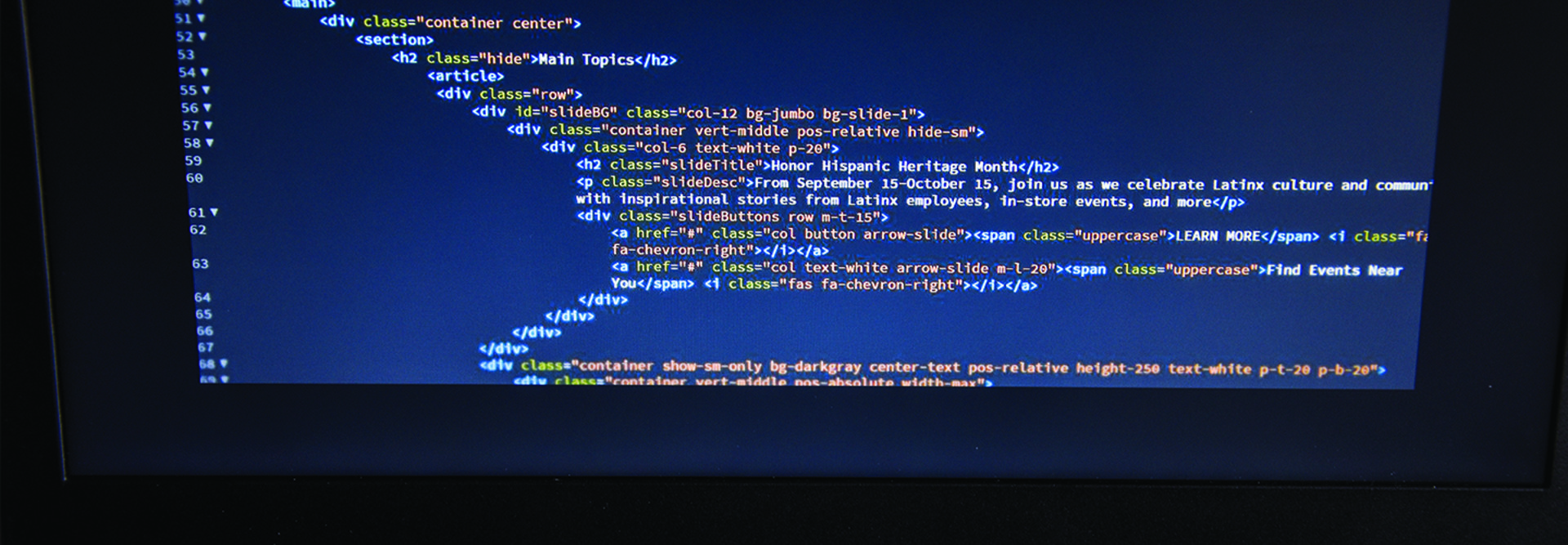

There are two different kinds of software coding that can affect your device. One is the group of applications that are loaded onto computers and smartphones before they get to the customer. Unflatteringly referred to as bloatware, this is that GPS app you can’t delete from your phone, or that game you can’t uninstall from your laptop. They take up considerable RAM on the device, hindering performance and draining battery life.

The reason this bloatware exists is simple: Manufacturers are paid by app developers to put the program on the devices. According to research from Pennsylvania State University, the money manufacturers get from app developers helps keep the costs of devices low, causing customers to buy them despite the unwanted programming. The researchers note that, as long as the market is willing to accept bloatware as a trade-off for less expensive electronics, it will continue.

Then there’s software bloat, which is when programs are loaded down with code built for tasks that a particular user doesn’t need. A study done by researchers at Stony Brook University found that most of this code was for functions that were disabled, making it particularly useless. Still, the extra code bogs down device functionality, causing other programs to run more slowly. Fatware is another term that customers use to describe these frustrations.

MORE FROM BIZTECH: Read how IT teams remain responsible for security in the cloud.

How Can Bloatware Affect My System?

The main way that bloatware affects systems is by slowing them down. The permanent applications and excess code take up space on the hard drive, interfering with everyday processes and functions. While it is tough to gauge exactly how much of an impact bloatware has, a line of PCs free of any third-party applications started up 104 percent faster, shut down 35 percent faster, and had 28 more minutes of battery life, according to its manufacturer.

Bloatware usually isn’t dangerous, merely inconvenient. But there’s renewed scrutiny amid recent personal data and privacy concerns. As Penn State researchers note, apps often run in the background of a phone or computer, collecting data such as GPS location, hardware identification numbers and phone numbers, with no clear way to know what’s being tracked — unsettling to device users.

While there may not be direct security concerns about software bloat, more code often means more fuel for hackers to weaponize. Stony Brook’s researchers point out that instruction sequences can be leveraged against users to create hacking tools, not to mention any potential security bugs that could be living in the code. Because the sequences aren’t used, it would be nearly impossible to find the bugs, making eliminating the code the best option for staying secure.