Fathers of Technology: 10 Men Who Invented and Innovated in Tech

When people are asked to describe inventors, they often use one word: genius. As a society, we look upon the inventor with awe, and we fawn over his inventions with curiosity and admiration. We wonder, how did he do that? Where did he find his inspiration?

In the course of IT history, certain men have breathed life into groundbreaking technologies that most users now take for granted. In honor of Father’s Day, and as a companion piece to our 10 Mothers of Technology, we’ve compiled a list of 10 men who have helped shape IT with their inventions. And for an updated look at some new fathers of technology and their impact on today's tech landscape, check out, “ The New Fathers of Technology: 6 Men Whose Innovations Shape Our World.”

Here’s a toast to 10 fathers of technology.

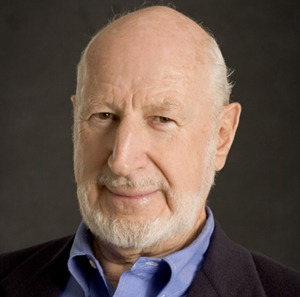

Douglas Engelbart

Human-Computer Interaction Whiz

His impact on technology:

Doug Engelbart is most celebrated for his role in inventing the mouse (along with his lead engineer at the Stanford Research Institute, Bill English, who fashioned the first mouse prototype). At a time when many people are turning to track pads and touch screens, the mouse remains perhaps the most commonly used peripheral of the past three decades.

But the mouse was a minor piece of Engelbart’s larger project, the oN-Line System. The unveiling of the NLS at the 1968 Fall Joint Computer Conference in San Francisco has been called “the mother of all demos” by some, because it packed video conferencing, networked collaboration, the mouse, hyperlinks and text editing into one presentation. These are now core technologies that make up what we think of as modern computing.

While the mouse proved to be a big hit with most, there was one man who questioned Engelbart’s design — specifically, how many buttons the mouse should have.

“We tried as many as five. We settled on three. That's all we could fit. Now the three-button mouse has become standard, except for the Mac. Steve Jobs insisted on only one button. We haven't spoken much since then,” Engelbart told Wired magazine in 2008.

Where is he now?

Engelbart’s mouse was too ahead of its time for him to profit from his idea. His patent expired in 1987, and he never received any royalties from it, according to the BBC.

After his famous demo in 1968, Engelbart remained at the Stanford Research Institute till 1977, when NLS and the Augmentation Research Center (ARC) were sold to a company that was ultimately acquired by McDonnell Douglas. He retired from McDonnell Douglas in 1989 and formed the nonprofit Bootstrap Institute, now known as the Douglas Engelbart Institute, an organization dedicated to promoting a collective approach to problem-solving. In 2007, he handed the reigns of the DEI over to his daughter, Christina Engelbart, and now serves as the institute’s director emeritus.

Words of wisdom:

“I made a decision to maximize my contribution to mankind. But what would I do? There were so many complicated problems in the world. Things were changing at such a large scale. I came to realize that we needed new levels of group understanding and abilities to work collectively to solve complex problems.” — Doug Engelbart on what drove him to invent in a Wired article

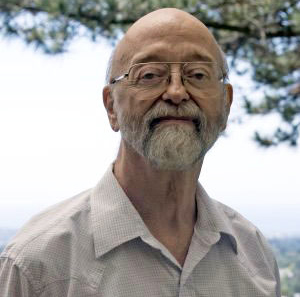

Norman Abramson

Wireless Hero

His impact on technology:

For technophiles, Hawaii is more than just a great place to surf — it’s also the birthplace of wireless LAN technology. Norm Abramson’s claim to fame lies in his achievements with the ALOHAnet, the first wireless local area network. Designed and developed by Abramson at the University of Hawaii, the ALOHAnet was the first network to transmit data successfully using radio signals — a fundamental technological breakthrough.

While Hawaii may be better known for its natural beauty than for its technological inventions, it actually makes sense that the wireless network was born there. Data transmission and IT resource sharing among the university’s campuses, spread across the state’s many islands, was essential. Abramson’s ALOHAnet used high-speed data packets, known as ALOHA channels, to transmit data over radio frequencies. ALOHA channels in particular have proved to be resilient technology, used in every generation of mobile broadband, from 1G to 4G.

Abramson’s ALOHAnet and its packet broadcast technology was a revolutionary advance over the switched-circuit data technologies of the time. Robert Metcalfe, who went on to develop Ethernet, spent considerable time with Abramson, studying the way that the ALOHAnet used data packets. Ironically, Abramson’s wireless technology helped lay the foundation for Metcalfe’s wired technology.

Where is he now?

Until his retirement, Abramson continued to work on the ALOHA protocols and packet broadcasting technologies in a commercial capacity as founder and CEO of Aloha Networks and Skyware. Now living in San Francisco, Abramson continues his research in ALOHA applications and communication theory, and spends his time writing and speaking about the history of ALOHAnet, he said to BizTech magazine.

Words of wisdom:

“It was becoming apparent that the existing telephone network architecture was not well suited to the rapidly emerging data networking needs of the 1970s. Indeed, it would have been surprising had such a network architecture, shaped by the requirements of voice communications at the end of the 19th century, been compatible with the emerging requirements of data communication networks at the end of the 20th century.’” — Norm Abramson on the need for a new data network in his "Development of the ALOHAnet" IEEE paper

Jack Nilles

Telework Titan

His impact on technology:

If your company has work-from-home Fridays, you can thank Jack Nilles. His efforts to define and promote the concept of telework is partially responsible.

People often jest that it “doesn’t take a rocket scientist” to figure out solutions to common problems. Telework, it turns out, did. Jack Nilles was working as a rocket scientist in the early 1970s when he was struck by the amount of congestion on the roads. He realized that the daily commute that people made just to get to work was responsible for the stress-inducing traffic everyone had to suffer through.

To Nilles, the answer was obvious: Get people off the road by removing the requirement that they come into the office to work. With that goal in mind, he began working with a team at the University of Southern California to design, define and test a telework initiative at an insurance company using satellite offices, Nilles said in an interview with BizTech magazine.

As he later found out, technology wasn’t the biggest obstacle in getting organizations and managers to accept telework — it was an old-fashioned mindset that work could only be done within the confines of an office.

“I learned early on that one of the key features of getting telecommuting going was patience and persistence,” Nilles told BizTech magazine. “Now we’ve got millions of people doing [telework], and they’ll even admit to it.”

Where is he now?

Nilles continues to promote telework through his consulting company, JALA International. While Nilles and JALA have achieved a significant amount of success domestically, he’s also hard at work in international circles, with projects in Lisbon, Portugal; Madrid; and Vienna.

Over the past 40 years, teleworking has grown from a wild and crazy idea to an acceptable way of life, but one sweeping change Nilles sees coming down the road is the revolution of the office space.

“Downtown areas better start thinking about redesigning their skyscrapers for multiuse, because the trend is going to be that people won’t want to go some great distance to get to work,” he says. “Downtown Los Angeles, we told them, if you don’t start redesigning things, you’re going to end up with a wasteland, and now there’s much more residential development in downtown LA.”

Aside from a decreasing need for large amounts of commercial office space, the nature of what people do in the office is changing as well.

“The nature of the office now has changed. The office now, for many, is a place for communicating face to face. You still need some of that,” Nilles says. “You don’t need as much cubicle space as you need conference space.”

Words of wisdom:

“It has always been the case from the very beginning that more people have location independent jobs than managers who will let them do it. So we’re always well below the point where everyone who can do [telework] does.” — Jack Nilles said in an interview with BizTech magazine

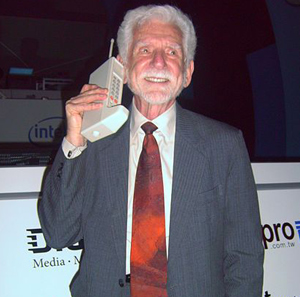

Marty Cooper

Mobile Magician

His impact on technology:

Marty Cooper’s invention — a bulky, gray 2-pound box — was no fashion statement. But without the Motorola DynaTAC, we would not have the sleek smartphones we swear by today. Sure, you could only talk on it for 35 minutes, but before the DynaTAC, the only option users had for making a call were telephones tethered to the wall.

As Cooper told the BBC, the team at Motorola had the unenviable challenge of figuring out for the first time how to pack all of the necessary technology into a self-contained mobile device. There was no blueprint upon which they could improve.

"We had to virtually shut down all engineering at our company and have everybody working on the phone and the infrastructure to make the thing work," Cooper said.

And to those who lament the cost of a 4G upgrade, Cooper offers this perspective: "Even by 1983, a portable handheld cellular telephone cost $4,000, which would be the equivalent of more than $10,000 today."

With today’s smartphones, of course, we do more than just talk. We send voice, text and video messages, take pictures, run applications, check the weather and watch TV, movies and more. Once Cooper took the phone wireless, the sky has truly been the limit for modern communication.

Where is he now?

In 1986, Marty Cooper and his wife, Arlene Harris, launched Dyna LLC, a company they founded to further their work in wireless technology. They’re probably best known today for their Jitterbug cell phones, which offer a simple user interface that has proved popular with senior citizens. Cooper and Harris also serve on the board of Jitterbug’s parent company, GreatCall, which offers a host of health, wellness and emergency mobile services.

Words of wisdom:

“I think that wireless has the opportunity to solve a whole bunch of problems, including, I believe, world poverty. So the two areas that I talk a lot about and really believe are important are the wireless impact on medical technology and on social networking. Both of those two things are going to be revolutionary.” — Marty Cooper on the untapped potential of mobile technology in an interview with The Verge

Gerald A. Lawson

Gaming Champion

Photo: Lawson family

His impact on technology:

Gerald Lawson created the first cartridge-based video game system, the Fairchild Channel F. That invention pushed the video game industry forward into a flexible, diverse future — a world in which games were no longer married to their hardware (think Pong). Once players could switch games on a whim, game developers and software companies flourished.

The Atari 2600, the original Nintendo Entertainment System, the Sega Master System and many other classic video game systems owe their fortunes in part to Lawson’s vision.

And yet, Lawson is not a well-known name in video game history — or tech history, for that matter. This, despite the fact that he was one of the few black members of the historic Homebrew Computer Club, which counted Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak as members.

Where is he now?

Lawson died last year of complications from diabetes. After spending eight years with Fairchild Semiconductor, the makers of the Channel F video game console he helped pioneer, Lawson left and started his own company, VideoSoft, which produced cartridge games for the Atari 2600, the system that ultimately made the Channel F obsolete.

Pong creator and Atari legend Allan Alcorn, who attended Lawson’s funeral service, spoke highly of his gifts, praising him as a “pioneer” and a true original.

Marc Lawson is following in his father’s footsteps as a senior product developer with NBA Digital. However, Marc is more of a software person, while his father was fond of hardware. Over time, Marc has grown to appreciate where his father was coming from.

“He came from an era of punch cards and assembly language programming, whereas I come from a world of C and Java and Objective-C, which is using libraries that actually talk to the hardware,” Marc told BizTech magazine.

“He would comment that ‘you guys don't really know what it is you're developing on.’ It's black box to us. So being programmers, we'll write code without even understanding the architecture of the underlying hardware and what we can really do with it, because programming is abstracted. As I got a little older, I started to get a little bit more into the hardware side of things.”

One interesting fact about Gerald Lawson: He actually wasn’t a huge gamer himself, his son said. He was more interested in the technology behind video games than in playing them.

Words of wisdom:

“The way we measure intelligence today is, if I have a hundred pounds of intelligence and I get from you 99 pounds, you're considered bright, right? My feeling is what ‘bright’ is or what ‘genius’ is — if I give you a hundred pounds of intelligence, you give me back 120. That means you take what you've taken and gone beyond that. You've learned other things, correlated the pieces, and put it together and added something to it. That's genius.” — Gerald Lawson on what genius means to him in an interview with VintageComputing.com

Nathaniel Borenstein

Attachment Architect

His impact on technology:

Long before cloud computing became a tech buzzword, almost everyone was using the cloud without knowing it.

Have you ever e-mailed yourself important files and used your inbox as an archive of sorts, going back to retrieve files as needed? Then you were using the cloud, courtesy of Nathaniel Borenstein, inventor of the e-mail attachment.

E-mail has always been quick, easy to use and reliable, and before the Facebook era, it was the primary method of sharing digital media such as scanned documents, photos, sound files and video. But even with the rise of Facebook and other social media applications, Borenstein’s invention, the Multipurpose Internet Mail Extension (MIME), remains popular, with an estimated trillion attachments sent each day in 2012, according to The Guardian.

You can hear the first e-mail attachment ever sent on Borenstein's site here. It's an audio file of Borenstein and his barber shop quartet singing about the glory of the newly invented MIME.

Where is he now?

After inventing the MIME protocol at Bellcore, Borenstein became intrigued with online payments. He moved on to First Virtual Holdings (the first cyberbank according to some) and later founded NETPOS.com.

After his stint in payments, Borenstein spent eight years with IBM as the company’s chief open standards strategist. He’s now moved across the pond to London to work as the chief scientist for Mimecast, a unified e-mail management company. You might say he’s returned to his first love in his current position.

Words of wisdom:

“Spam is bad. The amazing degree of unanimity that greets such a simple declaration is, paradoxically, the biggest impediment to progress in antispam standards.” — Nathaniel Borenstein on the trouble with fighting spam in a presentation to NIST/FCC

Robert Metcalfe

Ethernet Impresario

His impact on technology:

It would have been hard to imagine in 1977 — when Robert Metcalfe’s Ethernet received its patent — what a game-changer Internet access would prove to be with broadband as its fuel. Unlike dial-up networking, Ethernet transmits data at much higher bandwidths.

Robert Metcalfe’s journey to the creation of Ethernet started with Norm Abramson’s ALOHAnet. As part of his Ph.D. research, Metcalfe visited with Abramson’s team at the University of Hawaii to study what they had created — a wireless network using high-speed data packets to transmit data. Metcalfe took what he learned from Abramson and applied it to his work at Xerox in the company’s legendary Xerox PARC lab. Xerox officially filed for the Ethernet patent in 1975, listing Metcalfe, David R. Boggs, Charles P. Thacker, Butler W. Lampson as co-inventors.

Today, Ethernet has grown to immense sizes such as 10 Gigabit, 40 Gigabit and 100 Gigabit Ethernet, which allows for more than enough bandwidth to accommodate data-hungry technologies such as streaming video and applications in the cloud.

Where is he now?

After his time with Xerox, Metcalfe went on to start 3Com, a computer networking manufacturer. In 1990, he left the company and spent the next decade as a technology writer and pundit, writing a column for InfoWorld. He also serves as a venture partner for Polaris Ventures, a startup venture capital which has $3.5 billion under management. Polaris is the organization behind Dogpatch Labs accelerators, which gave birth to $1 billion-dollar startup darling Instagram.

Additionally, Metcalfe is now professor of innovation and Murchison Fellow of Free Enterprise in the University of Texas at Austin's Cockrell School of Engineering.

Words of wisdom:

“Technological innovation is the source of all progress. So you should be in the technological innovation business, at the core of which is science and engineering. It's the highest calling, to be in technological innovation. Democracy, freedom, prosperity, they all stem from technological innovation.” — Robert Metcalfe on the power of technology in an interview with the Computer History Museum

Tim Berners-Lee

Web Master

His impact on technology:

So profound is the global impact of Tim Berners-Lee’s invention that it’s hard to remember a time when common users worldwide could not communicate with one another instantly by computer. And yet, it was only 20 years ago that Berners-Lee created the World Wide Web.

When most people think of the Internet, they’re really thinking of the World Wide Web (WWW), the information superhighway that we navigate through a browser. Berners-Lee also invented the first web browser (called the WorldWideWeb at first but later changed to Nexus to avoid confusion); the hypertext markup language (HTML); and the hypertext transfer protocol (HTTP). These three components have made up what we consider the web for the past 20 years.

It all started in the European Particle Physics Laboratory at CERN with a memo that Berners-Lee sent suggesting a global hypertext system. His idea initially fell on deaf ears, but ultimately he got the go-ahead to experiment with a few NeXT computers, which he then used to bring his global hypertext idea to life. By 1991, Berners-Lee made the WWW available on the Internet.

Where is he now?

After ushering in the birth of the WWW, Berners-Lee has continued to play a leadership role in the web’s evolution. He founded and serves as the director of the World Wide Web Consortium, a nonprofit organization responsible for creating and maintaining web standards, such as HTML 5 and CSS 3. His accolades are numerous, but perhaps the highest honor was being knighted by Queen Elizabeth II of England in 2004 for his pioneering work in creating the WWW, granting him the lofty title of Sir Timothy Berners-Lee.

Words of wisdom:

“A very early and important point of the web is that there’s no line where you say these things belong on the web and these things don’t. The universality of it from the word go was very important.” — Tim Berners-Lee on avoiding silos on the web in a World Wide Web @ 20 interview

Dr. Fujio Masuoka

Flash Man

His impact on technology:

Flash memory is ubiquitous now, but there was a time when volatile memory technology such as DRAM and SRAM reigned supreme. The big downside of volatile memory? Once the power is turned off, the data is lost.

In the early 1980s, Dr. Fujio Masuoka dreamed of developing and perfecting a nonvolatile memory chip that could retain data even when its power source had been shut off. His breakthrough came in 1984, when Masuoka created NOR flash memory while working at Toshiba. His 4 megabit NAND-type flash memory was unveiled at the International Solid-State Circuits Conference in 1989.

Flash media now accounts for 95 percent of the blank storage media market, generating an estimated $4.8 billion in sales in 2010, according to the Consumer Electronics Association. The technology is now used to store data in cell phones, digital camera and USB flash drives.

Where is he now?

After developing flash memory, Masuoka didn’t find immediate superstardom. Toshiba at the time was largely unconvinced of the potential of flash memory, so the company gave him a small bonus and did little to take advantage of the lead it had with flash storage, according to a 2002 Forbes article.

Today, Masuoka leads a relatively quiet life as a professor at Tohoku University in Sendai, Japan.

Words of wisdom:

“Simply put, I wanted to make a chip that could one day replace all other memory technologies on the market.” — Dr. Fujio Masuoka on why he invented flash storage in a BusinessWeek article

Ken Thompson

OS Virtuoso

His impact on technology:

While DOS reigned supreme for much of the 1990s as the king of operating systems, as a 16-bit single-user OS it pales in comparison to UNIX, a multiuser 32/64-bit system developed by Ken Thompson more than 20 years earlier.

Thompson was part of a team of developers and researchers working at AT&T’s Bell Labs in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Early versions of UNIX were written largely by Thompson, but the breakthrough version of UNIX was rewritten with Dennis Ritchie in the C language in 1972.

Since then, UNIX and popular UNIX-like operating systems, such as Linux, Android and Mac OS, have built on Thompson and Ritchie’s legacy.

Where is he now?

Thompson continued at Bell Labs until 2000 and now works at Google as a distinguished engineer. He recently helped build Go, a new object-oriented programming language that he believes simplifies the unnecessary complexities of C++.

Thompson and his UNIX co-creator Ritchie have received several awards over the years for their UNIX invention, including the National Medal of Technology in 1999 and the Japan Prize last year.

Words of wisdom:

“I knew, in a deep sense, every line of code I ever wrote. I'd write a program during the day, and at night I'd sit there and walk through it line by line and find bugs. I'd go back the next day and, sure enough, it would be wrong.” — Ken Thompson on the innate nature of programming in the book Coders at Work

If you're looking for big names like Steve Wozniak and Bill Gates on this list, don't fret. They weren't forgotten. They'll be included in our next list, Great Founders in Biz Tech, so stay tuned.